This piece can be read in full on the Huffington Post Religion; it was co-authored with Valarie Kaur.

In the weeks following 9/11, a Sikh man named Balbir Singh Sodhi was shot down at a gas station by a man shouting “I’m a patriot!” In 2009, a 9-year-old girl named Brisenia Flores and her father were murdered in Arizona, allegedly at the hands of anti-immigration crusaders. And just last week, a gay activist named David Kato was bludgeoned to death in Uganda after his picture was published in a magazine article outing and encouraging the execution of LGBT individuals.

In the weeks following 9/11, a Sikh man named Balbir Singh Sodhi was shot down at a gas station by a man shouting “I’m a patriot!” In 2009, a 9-year-old girl named Brisenia Flores and her father were murdered in Arizona, allegedly at the hands of anti-immigration crusaders. And just last week, a gay activist named David Kato was bludgeoned to death in Uganda after his picture was published in a magazine article outing and encouraging the execution of LGBT individuals.

What do these three disparate acts have in common? They were rooted in fear and hate, represent humanity at its worst … and they brought together a 29-year-old Sikh woman and a 23-year-old gay atheist.

At first glance, we may seem an odd duo. One of us is a Yale law student and dedicated filmmaker who has spent years raising up the stories of people swept up in hate crimes, racial profiling and domestic violence since 9/11; the other is a queer interfaith activist from the Midwest with more tattoos than fingers, who is working to bridge the cultural divide between the religious and the nonreligious.

We first met in September of 2010, when Park51, or the “Ground Zero Mosque,” came under national scrutiny and a pastor gained prominence by threatening to burn Qurans on the ninth anniversary of the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Looking for a compassionate place to form a response in the midst of cultural strife and increasingly hateful rhetoric, we gathered in a living room and drank hot tea, brainstorming with a group of peers across the country over Skype and e-mail. The result was the Common Ground Campaign, a youth-led coalition speaking out against anti-Muslim bias. In a few short weeks, more than 1,000 people from all walks of life signed on to the Common Ground Campaign charter, and the movement continues to grow. Continue reading at The Huffington Post.

Announcing My February Speaking Tour!

January 27, 2011

This has been long in the works, so I’m excited to finally share the exciting news with you all: I’m going on a speaking tour of seven Midwest colleges and universities next month! At the invitation of campus staff and student groups from the following schools, I will be going from Indiana to Illinois to Iowa to speak about the importance of religious-atheist engagement, and the experiences that led me to the work I do around this issue.

This has been long in the works, so I’m excited to finally share the exciting news with you all: I’m going on a speaking tour of seven Midwest colleges and universities next month! At the invitation of campus staff and student groups from the following schools, I will be going from Indiana to Illinois to Iowa to speak about the importance of religious-atheist engagement, and the experiences that led me to the work I do around this issue.

Below is my itinerary — if you’re in the area for any of the “open to the public” events, please come by. I’d love to see you there! (And if you’re a student at one of these schools, I heard a rumor that some of your professors are offering extra credit in exchange for your attendance! Grades hitting a February slump? Come sit in the audience and pretend to listen while playing “Angry Birds.”)

February 2011 Midwest Speaking Tour

(Or, “What I’m Doing Instead of Taking a Vacation!”)

2/10: DePauw University | Greencastle, IN

- Meetings with the Interfaith group, LGBTQA group, and the Center for Spiritual Life

- 7:30-9:30 PM | Speech (open to the public)

2/11: Butler University / Indiana Campus Compact | Indianapolis, IN

- Meeting with the Indiana Interfaith Service Corps (AmeriCorps)

- Noon-1:30 PM | Speech / Luncheon (open to the public)

2/14: University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign | Urbana-Champaign, IL

- Meetings with student groups

- Luncheon — Facilitated Conversation

- Speech (open to the public)

2/15: Northwestern University | Evanston, IL

- 7 PM | Speech (open to the public)

2/16: Elmhurst College | Elmhurst, IL

- Meetings with student groups

- 11:30 AM | Luncheon — Facilitated Conversation

- 7 PM | Speech (open to the public)

2/17: DePaul University | Chicago, IL

- 6 PM | Speech (open to the public)

2/21: Simpson College | Indianola, IA

- Luncheon — Facilitated Conversation

- 5-7 PM | Speech (open to the public)

Interested in having me come speak? Email me at nonprophetstatus [at] gmail [dot] com!

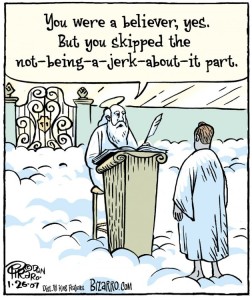

The Religious Must Stand Up for Atheists

January 26, 2011

Today’s guest post is by Joshua Stanton, a man I am lucky to call both a good friend and a colleague at the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue in my work as the Managing Director of State of Formation. In this post, Josh offers a thoughtful, personal reflection on why it is essential for the interfaith movement to stand up against anti-atheist rhetoric and action in the way that it does when particular religious communities come under fire. As an atheist, I couldn’t appreciate this post more. Many thanks to Josh for his important perspective, and for using his voice to advocate for people like me. Without further ado:

The interfaith movement is beginning to rack up successes. While outbursts of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia (among other expressions of prejudice against religious communities) are nothing new, the growing and remarkably diverse chorus of voices trying to drown bigots out certainly is.

The interfaith movement is beginning to rack up successes. While outbursts of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia (among other expressions of prejudice against religious communities) are nothing new, the growing and remarkably diverse chorus of voices trying to drown bigots out certainly is.

To take but one recent example, when the Park51 Muslim community center in Lower Manhattan was subjected to undue criticism this past summer, the groups that gathered behind closed doors to support its besmirched but beloved leaders included atheists, Jews, Christians, Muslims and more. It was heartening — as were the rallies led by Religious Freedom USA and New York Neighbors for American Values, which drew thousands to the streets to support the rights of all religious communities to assemble on private property. You could feel the interfaith movement surging forward on its remarkable course.

But I am uncertain, if not outright skeptical, that members of the interfaith movement would equally protect non-religious communities that come under similar scrutiny. To take a personal (and rather confessional) example, when a friend was excluded from an interfaith peace-building initiative because of being non-religious, people told him they were sorry. But nobody refused to continue participating in the group. It just didn’t seem like a reason to protest the decision or leave the group altogether.

I am among those guilty of not speaking up — cowed by diffusion of responsibility and the glow of opportunity that the group provided. I am certain, based on the numerous stories my humanist and atheist friends have told me, that this was not an isolated occurrence, nor an unusually cowardly reaction on my part. Yet it is something for which I am still performing teshuvah — answering as a Jew and human being for wrongdoing to my friend, in this case through wrongful inaction.

Why is it that when someone criticizes or excludes atheists, it feels like the interfaith movement forgets its identity, if only for a split second? Why is it that well-meaning interfaith leaders defy their identities and fail to speak out against those who threaten or undermine the status of the non-religious? Individually, we may comfort our friends, but by and large we are not sticking our necks out, writing op-eds, holding protests and publicly condemning those who single out the non-religious.

In part, I would suggest that members of the interfaith movement have not yet developed reflexes for protecting the non-religious. There is somewhat less of a history of hatred for atheists in the West (and even less education about the hatred that has been made manifest), so it does not always register in our minds when someone speaks ill of atheists in a way that it would if someone spoke similarly about people of a particular religious group.

But guilt for the repeated historical failure of Western countries to protect religious minorities is hardly an excuse for inaction in the present to protect the non-religious. It is time that we, most especially in the interfaith movement, recognize, denounce and speak out against anti-atheist bigotry.

Admittedly, many religious individuals feel intellectually and theologically challenged by atheists. But this challenge is one we must greet and learn from, rather than respond to with aggression, passive and active alike. If God is truly powerful, non-believers can hardly break our belief, much less the Divine we believe in. If God is loving, then why should we hate — or ignore hatred directed towards others? If God is a Creator, how can we allow others to speak ill of the atheists and non-believers God gave life to? Non-belief is a reality for hundreds of millions of people around the world, and the religious can hardly condemn atheists without running into contradictions rendered by their faith.

If religious affiliation is a protected category in our laws, our minds and our actions, so too must non-affiliation and atheism. The interfaith movement must lead the way, and so too must its believing members. They — we — cannot allow this double-standard to persist.

This post originally appeared on The Huffington Post Religion.

Joshua Stanton serves as Program Director and Founding co-Editor of the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue at Auburn Theological Seminary and co-Director of Religious Freedom USA, which works to ensure that freedom of religion is as protected in practice as it is in writ. He is also a Schusterman Rabbinical Fellow and Weiner Education Fellow at the Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City.

Joshua Stanton serves as Program Director and Founding co-Editor of the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue at Auburn Theological Seminary and co-Director of Religious Freedom USA, which works to ensure that freedom of religion is as protected in practice as it is in writ. He is also a Schusterman Rabbinical Fellow and Weiner Education Fellow at the Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City.

Do Only Religious People Have a ‘Calling’?

January 25, 2011

Please check out my latest piece for the Huffington Post, currently featured at the top of their Religion section! Below is a selection; it can be read in full at the Huffington Post:

In a recent interview with BBC Radio 4, musician Jack White (of the White Stripes and other bands) reflected on his “calling.”

“I was thinking at 14 that possibly I might have had the calling to be a priest,” said White. “Blues singers sort of have the same feelings as someone who’s called to be a priest might have.”

That he connected his sense of a calling to a career in ministry isn’t surprising. The word “calling,” or “vocation,” has explicitly religious roots; derived from the Latin vocare, or “to call,” the terms originated in the Catholic Church as a way of referring to the inclination for a religious life as a priest, monk, or nun. During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther broadened the term beyond ministry to include work that serves others, but still couched it in a religious framework.

Today, “calling” has become common currency in the American parlance, its meaning expanded to refer to the realization of an individual’s passion or drive. Though the term has long had religious associations, it is used just as often to refer to secular work as it is religious.

Still, there’s something more to a calling — something almost otherworldly.

What’s Your Calling?

January 21, 2011

In partnership with the PBS documentary The Calling, a campaign called What’s Your Calling? was launched to explore the topic of a “calling.” I was honored to be invited to do an interview with them; in our interview, they asked me to talk about my “calling,” so I shared a bit of my story and discussed my hope for greater nonreligious-religious dialogue and cooperation.

Using this interview, they produced the above video (full of old, embarrassing photos, haha). Please check out their page on my video, browse their site to watch other videos, and join their important conversation.

P.S. I’ve written a piece on atheism and calling / vocation; it should be out relatively soon, so stay tuned!

God, We Need Atheists

January 19, 2011

Today’s guest post, by my friend Frank Fredericks (Co-Founder of Religious Freedom USA and Founder of World Faith), addresses the gaping cultural divide between Christians and atheists. Like Amber Hacker’s NonProphet Status guest post, “A Committed Christian’s Atheist Heroes,” Frank writes as a dedicated Christian interested in finding ways to work with and better understand his atheist friends and neighbors. As someone who knows Frank and respects his work, I’m delighted to share his thought-provoking reflection here. Take it away, Frank:

The discourse between evangelical Christians and atheists has been antipodal at best. Whether it is Richard Dawkins calling faith “the great cop-out,” or countless professed Christians using “godless” like an offensive epithet, we’ve reached new lows. In fact, generally the discussion quickly descends into a volley of talking points and apologetics. I abhor those conversations with the same disdain I reserve for being stuck in the crossfire between a toe-the-line Republican and slogan-happy Democrat, rehashing last week’s pundit talking points.

The discourse between evangelical Christians and atheists has been antipodal at best. Whether it is Richard Dawkins calling faith “the great cop-out,” or countless professed Christians using “godless” like an offensive epithet, we’ve reached new lows. In fact, generally the discussion quickly descends into a volley of talking points and apologetics. I abhor those conversations with the same disdain I reserve for being stuck in the crossfire between a toe-the-line Republican and slogan-happy Democrat, rehashing last week’s pundit talking points.

I believe we need to revolutionize the way we interact. As an evangelical Christian, I recognize that my community equates atheism with pedophilia, like some dark spiritual vacuum that sucks out any trace of compassion or morality. Even in interfaith circles, where peace and tolerance (and soft kittens) rule the day, the atheists are often eyed with suspicion in the corner — if they’re even invited.

I thank God for atheists. During my college years at New York University, I had the superb opportunity to have powerful conversations with atheists who challenged me to have an honest conversation about faith. I appreciate and a value how atheist friends of mine encouraged inquiry. Remarkably, while this may not have been their intent, it only strengthened my faith. While I was able to begin weeding out the empty talking points from the substantive discourse, I hope they also got a glimpse of the love of Christ from an evangelical who wasn’t preaching damnation or waiting to find the next available segway into a three-fold pamphlet about how they need Jesus in their life. The point is, Christians need to stop seeing their atheist neighbors, co-workers, and even family members as morally lost, eternally damned, or a possible convert.

What lies at the bottom of this is the assumption, as pushed by many Christian leaders, is that religious people have the monopoly on morality and values. That, in a sense, you can’t be good without God. This is troubling on several levels. While at first glance this seems theologically sound to assume the traditional concept of salvation, most haven’t grappled with the problematic idea that Hitler could be in heaven and Gandhi could be in hell. That should be troubling for us. Also, the cultural and social ramifications of this leads to an antagonizing relationship. The Bible is littered with examples of non-religious, non-Christian, or non-Jewish people who do good in the eyes of God. It shouldn’t be shocking to see atheists teach their children integrity, or volunteer in a soup kitchen.

While I reserve the bulk of my frustration for those misusing my own faith, atheists aren’t blameless in this tectonic paradigm. Rather than taking the inclusive road of respectful disagreement, many of the largest voices for atheism find it more enjoyable to belittle faith, mock religion, and disregard their cultural and sociological value. In fact, many consider it their duty to evangelize their beliefs with the same judgmental fervor they fled from their religious past. Knowing that many came to define themselves as atheists against rigid religious upbringing, I don’t judge their disdain and frustration. However, like venom in veins, it keeps them from moving forward to having a more productive discourse. So often, when the religious and non-religious traditions grapple with the big question, like ontological definition, theorized cosmology, or the inherent nature of man, these discussion happen separately, without an engagement that is both fruitful and intriguing. I know many of those atheists have something wonderful to bring to that discussion, if they would stop throwing rocks at the window and come sit at the table.

So this is what I propose to my Christian and atheist friends: If we Christians challenge ourselves, our communities and congregations, to treat our atheist brothers and sisters as equitable members of our communities, nation, and in the pursuit of truth, will atheists recognize the value of faith to those who believe, even while they may respectfully disagree? As atheism quickly becomes the second largest philosophical tradition in America, the two communities will only have a greater need of a Memorandum of Understanding to frame how we can collectively work together to challenge the greater issues that face us, which starts by recognizing that it’s not each other.

Not sure where to start? Let’s feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and protect human dignity. While community service can be utterly rational, I am also pretty sure Jesus would be down for that, too.

Frank Fredericks is the founder of World Faith and Çöñár Records; in his career in music management, he has worked with such artists as Lady Gaga, Honey Larochelle, and Element57. Frank has been interviewed in New York Magazine, Tikkun and on Good Morning America, NPR, and other news outlets internationally. He also contributes to the interView series on the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue. He currently resides in Astoria, New York, leading World Faith and working as an Online Marketing Consultant.

Frank Fredericks is the founder of World Faith and Çöñár Records; in his career in music management, he has worked with such artists as Lady Gaga, Honey Larochelle, and Element57. Frank has been interviewed in New York Magazine, Tikkun and on Good Morning America, NPR, and other news outlets internationally. He also contributes to the interView series on the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue. He currently resides in Astoria, New York, leading World Faith and working as an Online Marketing Consultant.

Now is Not the Time for the Blame Game

January 17, 2011

Today’s guest post is a submission from Nico Lang, a regular NPS contributor. An intern at the Interfaith Youth Core and a senior at DePaul University, Lang co-founded the Queer Intercollegiate Alliance and is head of campus outreach for the Secular Humanist Alliance of Chicago. His previous writing for NPS includes”Through Common Struggle, Hope,” “Talking the ‘Hereafter’ With Atheists and Believer,” as well as posts on his personal journey as a queer agnostic interested in interfaith work, about Park51 and the state of American dialogue and on the ramifications of “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day.”

On January 8th, I found out about the shooting of Representative Giffords the same way that most millenials probably did: through a Facebook status update.

On January 8th, I found out about the shooting of Representative Giffords the same way that most millenials probably did: through a Facebook status update.

At a sharp 3:00 P.M., Cormac Molloy was “shocked that someone shot rep. giffords!”

Initially, I sat unfazed, as the constant barrage of celebrity and semi-celebrity Facebook eulogies can leave even the most dedicated techie in a stupor. I didn’t know whom Giffords was, who shot her or what state she represented, and so I let the moment pass me by with a simple refresh.

However, what my mini-feed would soon explain was that on that very morning, a man by the name of Jared Loughner shot Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, D-Ariz. As a Congresswoman, Giffords was many things: the fair-skinned wife of an astronaut, a Democratic holdout in an increasingly conservative state, and, most unfortunately, the object of a deranged man’s obsession.

Five were slain that day by Jared Loughner and two injured, and years from now, none of us will remember where we were when we heard the world was looking for answers. If we ask others about the events that took place that day, what will matter was how you followed the tragedy and what outlets you listened to.

Just hours later, as the world attempted to put the pieces together, we began to assign blame based on scattered details of a murderer’s life, the political affiliations of those involved or a misbegotten map that placed crosshairs over her district.

For the Fox News inclined, Jared Loughner was a “radical leftist.” However, the left saw him as a mobilized Tea Partier, and many of my friends labeled Giffords a victim of Sarah Palin’s violent rhetoric. For them, Giffords quickly became just another casualty in an increasingly toxic American political culture.

Through times of turmoil, many people look to the Seven Stages of Grief for guidance, which can be a telling way to define our trauma. In coping with the violence that erupted in Arizona, Americans quickly moved to that third stage, a place of anger. However, if we as a people desire to move from our initial shock to that final stage of hope, we must do much more than what the next stage asks of us, which is to simply reflect.

We must fully examine the state of our national anger.

Oddly enough, this is exactly what I was doing when I found out about the Giffords attack. When the bullets struck, I was researching the birther movement, a political substratum comprised of individuals who believe that Obama was not born in America, despite evidence to the contrary. For the unfamiliar, many of these citizens likewise resolutely believe that Obama is a Socialist, Hitler, the anti-Christ or any combination of the three.

In researching the role that such opinions might play in their lives, I concluded that such mechanisms allowed birthers and their ideological cousins to deal with the trauma of the 2008 elections. I found a people not only venting on message boards, but I also saw them coping with the fear of a president and an America that no longer looked they did. Out of this chaos, they constructed meaning. They made someone responsible. They found someone to hate.

Although a recent Time article suggested that we are most likely to believe negative information about others when they are of another race or religion, the problem runs deeper than that. When I hear that an online petition is “circulating to [indict] former Alaska governor Sarah Palin for incitement to violence,” I know that such mourners are seeking more than answers or resolution.

They are seeking blood.

At this time of crisis, we should ask questions about the state of America today, but making our neighbors into sworn enemies will never us help to comfort the grieving or make our nation stronger. After September 11th, the Fort Hood massacre, and the Park51 controversy, demonizing Muslims didn’t make us any safer and likely alienated potential allies and radicalized potential friends. Thus, if we continue to make America into a nation divided, we will likely incite the very extremist violence many seem to believe this tragedy is a symbol of.

On his Monday broadcast, Jon Stewart instead asked Americans to use this moment as an opportunity to envision a better world, one not defined by the hatred and name-calling that defined our nation over the past week. We will never know what demons drove Jared Loughner to pull the trigger that morning, but we cannot heal by continuing to invest in our own partisan phantoms.

As a nation, we have the ability to tear down the divides that ail us, and at a time when ideologies drive us apart, we must remember to live the example of Dorothy Day, the immortal founder of the Catholic Worker. On the subject of political divides, the once Communist Day famously remarked that she gave up the revolution because it kept her from loving her neighbor. According to her, the more meaningful challenge was instead how to bring out a revolution of the heart.

Recently, reports indicate that Gabrielle Gifford finally opened her eyes. Let us hope that our grief-blinded country can soon do the same.

Nico Lang is the Communications Intern for Interfaith Youth Core and a Senior in International Studies at DePaul University. Nico just started up DePaul’s first film club, the DePaul A.V. Club, and represents the lone agnostic among 2010-2011′s Vincent and Louise House residents, who represent DePaul’s Catholic intentional living and social justice community. He is also the co-founder of the Queer Intercollegiate Alliance, an initiative between Chicago’s LGBT campus groups; a writer for the DePaulia newspaper; and head of Campus Outreach for the Secular Humanist Alliance of Chicago. Occassionally, Nico sleeps.

Nico Lang is the Communications Intern for Interfaith Youth Core and a Senior in International Studies at DePaul University. Nico just started up DePaul’s first film club, the DePaul A.V. Club, and represents the lone agnostic among 2010-2011′s Vincent and Louise House residents, who represent DePaul’s Catholic intentional living and social justice community. He is also the co-founder of the Queer Intercollegiate Alliance, an initiative between Chicago’s LGBT campus groups; a writer for the DePaulia newspaper; and head of Campus Outreach for the Secular Humanist Alliance of Chicago. Occassionally, Nico sleeps.

A Humanist Resolution to Overcome the Faith Gap

January 14, 2011

Please check out my latest blog for the Huffington Post! Below is a selection; it can be read in full at the Huffington Post:

It may be mid-January, but I’m still thinking of Christmas.

It may be mid-January, but I’m still thinking of Christmas.

The week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve just might be my favorite of the year. It is the one time that my entire family gets together. We spend several days eating our favorite foods, catching up and playing board games.

I’m the only member of my family who doesn’t live in Minnesota — I moved away several years ago — so that week is particularly special for me. While the snow piled up outside, I stole my 7-month-old nephew from his doting grandmother and smooshed his face into mine, worked on an unsolvable puzzle with my siblings and ate way too many cookies.

As I was getting ready to leave for the airport, my dad’s girlfriend stopped me at the door. “I’ve been wanting to ask you something,” she said, leaning in. “I know you’re an atheist, but is it OK for me to say ‘Merry Christmas’ to you?”

Time to Stop Rewarding the Dehumanizing Rhetoric

January 13, 2011

Recently, I was honored to receive an invitation to join the esteemed panel of the Washington Post’s On Faith. Please read and share my first piece — below is the beginning, and it can be read in full at On Faith:

In the wake of this national tragedy, many have speculated about whether violent rhetoric and imagery used by Sarah Palin and others directly influenced Saturday’s devastating events. We may never know if there was a direct link between Palin’s words and the tragedy in Arizona, but as Stephen Prothero eloquently argued this week, we shouldn’t hesitate to reflect on the impact of the rhetoric used by those with political influence.

In the wake of this national tragedy, many have speculated about whether violent rhetoric and imagery used by Sarah Palin and others directly influenced Saturday’s devastating events. We may never know if there was a direct link between Palin’s words and the tragedy in Arizona, but as Stephen Prothero eloquently argued this week, we shouldn’t hesitate to reflect on the impact of the rhetoric used by those with political influence.

As the news broke on Saturday morning, I was in the middle of writing about something Palin had written in her most recent book, America By Heart: Reflections on Family, Faith and Flag – specifically, her claim that “morality itself cannot be sustained without the support of religious beliefs.” Unlike the moral outcry inspired by her demands that “peaceful Muslims” “refudiate” the “Ground Zero Mosque,” her comments about the nonreligious were met with silence.

Sure enough, some on the political right are using this same logic to explain the actions of the alleged gunman, Jared Loughner. Said one right-wing pundit: “When God is not in your life, evil will seek to fill the void.”

A Newer Atheism: The Case for Affirmation and Accommodation

January 6, 2011

NonProphet Status’ first guest post of 2011 is by Andrew Lovley, founder and former chair of the Southern Maine Association of Secular Humanists (SMASH). Below, Lovley, who previously defended the invocation he performed at the inauguration ceremony for new city officials in South Portland, Maine, weighs in on the “accomodation vs. confrontation” debate and offers a thorough and impassioned case for positive and engaged atheism and humanism. This is among the best explications I’ve read on this topic and, though it is lengthy, it is well worth your time and I encourage all of you to read it in its entirety. Many thanks to Andrew for composing this, and for inspiring me (and, I’m sure, many others) with your words.

Atheist activism is at a crossroads. Atheism has arguably gained more attention in recent years than ever before, thanks to a concerted campaign by secular individuals and organizations to raise awareness as well as their frequent contribution of ideas and perspectives to the national discourse.

Atheist activism is at a crossroads. Atheism has arguably gained more attention in recent years than ever before, thanks to a concerted campaign by secular individuals and organizations to raise awareness as well as their frequent contribution of ideas and perspectives to the national discourse.

Yet as secular individuals, we must ask ourselves: How has this attention served us thus far? How could this attention be best utilized? The answers to these questions and an honest appraisal of our efforts rely on a consensus of what our goals are as a movement. Our increased salience in society affords us an unprecedented opportunity to realize our public activist goals, if we can manage to agree on what those goals are.

Virtually all atheist activists agree that we should promote science and critical thinking, encourage society to be more accepting of atheists, and try to provide support for atheists who have already elected to step out and brave the torrent of social stigma and castigation. Where a consensus manages to evade us however is in regards to our relationship with the religious communities by which we find ourselves surrounded.

Some suggest that we should focus our efforts toward making society less religious by actively trying to persuade people away from religion, while others believe we should work toward toleration and coexistence with our religious neighbors. Until atheist activists achieve some sort of consensus on this issue, we will continue to contradict each other in words and in actions and threaten our relevance as a movement.

It is time we make a prudent choice about how we should relate to religion and its adherents. Our movement’s vitality, and our success at achieving our goals, is being undermined by our too-often acerbic and pretentious attitudes. It is time we recognize that the secular movement and its members are best served by acting on an agenda that balances affirmation of our identity and values with conciliation toward the religious.

Generally speaking, the attitudes that shape the interactions between atheists and theists are characterized by mistrust, mockery, and vilification. Yet these attitudes do nothing to further our cause and become obstructions in themselves. Even if/when theists direct these attitudes toward us, we are better off not reflecting them. Let us lead by example by acting on humanist principles, and give those who deride our motives and actions no factual grounds upon which to base their biting criticisms. Angry and bitter atheist activists serve only to enflame the negative stereotypes we are plagued by. Atheist activists, who rhetorically exacerbate our differences and vilify theists in general, only encourage those theists to do the same and ultimately foster greater alienation of atheists. We are sometimes accused of intellectual hubris, and other times accused of possessing a sense of moral righteousness. These are not appealing qualities, and if we want more respect in the societies we find ourselves in we should abstain from having such attitudes.

Let us gain respect by respecting. Let us be tolerated by being tolerant. The Humanist Manifesto offers a great piece of democratic wisdom when it suggests that we should tolerate different but humane views. Too many atheist activists assert that giving any positive recognition to religion somehow makes one less of an atheist, or an accommodationist – a charge that only has respect in divisive and antagonistic circles. It may be accommodationist to acknowledge praiseworthy actions and services carried about by people inspired by their religion, but it is certainly no less atheist to do so, it is honest. The accommodation of different yet peaceful life-stances is a justified practice; in fact it is the glue and grease that is necessary for a civilized democratic society to be sustained. It is not a disparaging term, but rather a civic compliment.

Perhaps the most pervasive and frustrating mistake many atheist activists make is presenting an overly reductionist conception of religion in their critiques. What religion is reduced to is not always the same, but more often than not religion is spoke of as if it is merely a collection of falsehoods about the world, a reverence for mythical figures, and/or an act of willful ignorance called faith. Yet any real exposure to religion and religious people should lead one to recognize that religion means a whole lot more to people than the simple belief in the theology; in fact the theology may not even be the most important aspect of the religious experience. It may be convenient to level charges against religion by reducing it to theology, because it is most vulnerable to scientific and philosophical advances. Other important aspects of religion, however — such as the community it creates, the social work it encourages and fosters, the spirituality it engenders through collective singing and shared worship, the psychological preparedness and remedies for common struggles — aren’t the least bit disagreeable and that is probably why they are conveniently ignored in strident atheist criticisms.

Not only is religion in general a victim of straw-man arguments, but so is the diversity of religions and religious people. We must not make the naïve assumption that all religions are the same. Defining religion has been a difficult, if not impossible task for generations, precisely because of the diversity of structures, beliefs, and practices of the world’s religions. Atheist activists often speak of religious people as if they are all dogmatic, anti-science, anti-reason, evangelical social conservatives, an overgeneralization that is wont to needlessly offend the multitudes of moderate, liberal, and / or modern religious peoples out there. We must refrain from engaging in extreme moralization whereby all religious people and their behavior is considered disingenuous at best and repugnant at worst, and believing that atheism is the only justified and morally superior lifestyle.

Historically, the atheist agenda has primarily served to question the established orthodoxies of the time and to promote critical and scientific thought. Presently, however, many are going a step further to try and ‘deconvert’ religious people, a venture that is not only unnecessary but routinely counterproductive. Activist atheist attitudes that are especially condescending have the effect of nullifying the persuasiveness of their claims, regardless of the facts upon which they are based. Confrontational atheists are virtually ineffective at persuading theists that they are wrong, and the atheist’s efforts seem to further entrench theists in their beliefs and attitudes – not to mention increasing their distrust and/or contempt for atheists.

However if atheist activists insist on the critical urgency to draw theists away from their religious beliefs and practices, they would prove far more successful were they to revise their tactics. Theists with strong convictions are for all intents and purposes immune to rational criticism. Wavering theists, on the other hand, perhaps already burdened with doubts regarding the veracity of religious teachings, may be more responsive to atheist critiques if those critiques were supplemented with alternative (i.e. naturalistic) ways of addressing life’s existential and ethical questions. If we are preoccupied with ridiculing religion and its adherents, we are missing genuine opportunities to demonstrate the strength and comprehensiveness of secular humanism. On a similar note, wavering theists will be far more likely to join our ranks if they sense they can be associated with a positive and constructive crowd, not having to choose between the camaraderie of religion and the tenuous animosity of atheism.

A question atheist activists must address is: Would the world necessarily be a better place if all people were atheists? Atheist activists will sometimes espouse the idea that a merciless pursuit of objective knowledge and an abandonment of all unfounded truth assumptions will necessarily lead to a better society. This notion itself is quintessential modernist dogma and ignores the practical experience of belief. The personal benefits of belief come not from the beliefs being based in objective truth per se, but instead from the perception that those beliefs are based in truth – they come from certainty not objective veracity. An honest reflection upon this question of an atheistic society should conclude that no, it would not necessarily be a better one to live in. Atheism by itself does not produce the sustenance that a healthy society thrives on. Democracy, compassion, justice, and progress are not derivatives of atheism. As atheist activists we should recognize that these are in fact humanistic values.

If atheist activists care about progress and the betterment of the human condition, perhaps the ‘deconversion’ of theists should not be prioritized, but instead the promotion of humanistic values. Our socio-political agenda should not include or be premised on the universalization of our atheistic world-view. If the movement is more than apologetics and includes prejudice and proselytization, it is more destructive than worthwhile. Theists can be and often are humanists too, and society is better off for it. Atheist (or secular) humanists and theist humanists each find extremist ideology repulsive and dangerous, and should be willing to work together in stifling its spread.

Contrary to what many believe, atheists and theists alike, a civil and progressive society is possible where atheists and theists live together harmoniously. When atheists and theists get to know each other better, unencumbered by and disabused of stereotypical notions of each other, they often discover that they share many important values. Atheists should be willing to recognize this, and encourage alliances with theists on socio-political issues where they share similar sentiments and goals, including but not limited to the separation of church and state, stewardship of our planet, civil liberties, social services, and curbing extremism. Atheist activists need not be hyperbolic when discussing the fate of science and rationality either, because honest observers will notice that many worthwhile scientific and philosophical contributions have been made by theists or deists. We need not pretend as if we are bound up in some Manicheistic battle between good and evil, a battle between the non-religious and the religious, and adopt the false dichotomies that are typically conjured up in theology. We can live and prosper with those who do or do not believe in god; more importantly, we cannot afford to ignore those who have no respect for human dignity.

Atheist activists should reconsider their priorities and reevaluate their efforts. A sign of maturity for any group is a focus on what they are for rather than what they are not. It often seems as though atheist activists direct more of their attention to religious people rather than to fellow atheists. We are doing ourselves a disservice when we are preoccupied with critiquing religion instead of engaging in dialogue about how atheists can lead positive, fulfilling lives and contribute to a better world.

Let us direct more of our efforts toward helping secular people address the concerns of being secular and human such as death, anxiety, purpose, hope, relationships, parenting, etc. Let us devote more energy toward building up our own monuments rather than tearing down others. Let us affirm our identities and our values in an honest, yet tactful manner. If we want atheists to enjoy a better place in society and to have access to the resources they need to have fruitful lives, then we need to think carefully about our agenda and how we conduct ourselves as public activists.

Andrew Lovley is the founder and former Chair of the Southern Maine Association of Secular Humanists, a student organization at the University of Southern Maine. He holds a B.A. in Psychology, and is currently acting on his humanist values by serving in AmeriCorps as a tutor and mentor in Spokane, Washington.

Andrew Lovley is the founder and former Chair of the Southern Maine Association of Secular Humanists, a student organization at the University of Southern Maine. He holds a B.A. in Psychology, and is currently acting on his humanist values by serving in AmeriCorps as a tutor and mentor in Spokane, Washington.