The Assault on Dialogue: Thoughts on Park51

October 18, 2010

Today’s guest post in our ongoing series of guest contributors comes from Nicholas Lang, who previously submitted a guest piece reflecting on the ramifications of “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day.” In today’s post, Nick considers Park51 and the state of American dialogue. This one’s lengthy but is totally worth your time — take it away, Nick!

America is a nation of 300 million experts.

America is a nation of 300 million experts.

This phenomenon is everywhere. For proof, see: news articles that ask high school students their thoughts on world affairs. News channels composed of all talking heads and no news.

Although we may not be the nation composed of the best and brightest, as any study on public education systems will tell you, research shows that America turns out the most self-confident people in the world. We are a nation of certainty, of seemingly impenetrable ideological divides. For instance, a study by Columbia University professor Lisa Anderson showed that the September 11th attacks only served to strengthen Americans’ previously held political views. Whatever media you consumed defined how you viewed the events that transpired that day.

Thus, our ideological lenses define this certainty. We are a nation so cocksure that we will die for our beliefs. We will fight bloody, protracted wars for our beliefs. Furthermore, in the Age of the Global Media Village, we will argue endlessly on television about them. And Lindsay Lohan notwithstanding, what issue has been argued more extensively as of late than that insidious “Ground Zero Mosque?”

The Park51 (aka Cordoba House) debate seems to be the topic du jour just about every nuit, confounding the talking heads, setting the blogosphere on fire and making my “Park51” Google Alerts go crazy. If you have been living under a rock, here’s the deal: a guy named Imam Faisal wants to build an Islamic community center, which will feature a gym, a restaurant and a mosque… near Ground Zero.

This building will not be visible from Ground Zero and will revitalize the empty Burlington Coat Factory store annihilated by 9/11 debris, but this is all moot. As any lawyer can tell you: it’s not about the facts, it’s about the argumentation.

For instance, check out a recent piece by Glenn Beck and friends, thankfully available for viewing on GlennBeck.tv. What you will see is commentary on a Special Report by Keith Olbermann; however, Beck offers oddly little in the way of genuine commentary or analysis. Watch the clip and then name me five actual criticisms he has of Keith Olbermann’s actual rhetoric. Can you even name two? I watched it twice and had a hard time remembering one.

In the interests of fairness, Keith Olbermann’s program falls prey to many of the same tendencies as Beck’s: the targets just differ. While I like Olbermann considerably and find his reasoning sound and his facts to be accurate, he has a proud history of disengaging the issue. The basic structure of an Olbermann broadcast is meant to simulate discourse without the risk of actual conversation. The format runs as follows: K.O. shows a clip of someone he doesn’t agree with, talks about how he doesn’t agree with them and then brings on another person who doesn’t agree with them either. Lather, rinse, repeat ten times. Show’s over. We all get paid. Even in Special Reports like the one above, he engages in highly effective polemics, but what debate has actually taken place here?

In no case are the opponents on equal playing fields, as the end goal is not dialogue or discussion but simply to look right. As a liberal-minded chap who relishes relieving his TiVo of episodes of Real Time with Bill Maher, my poor, sweet Bill is no better. He never brings on ideological opponents he cannot crush; he never engages in a debate he cannot win. Did you see his documentary on faith, Religulous? Man, those poor religious folks were sitting ducks. Not even once did Bill interview someone who could truly engage him. Michael Moore is even worse. Are his documentaries entertaining and uncommonly riveting? Absolutely. But Moore is a filmmaker and entertainer above all else; he’s not a journalist or even much of a fact-checker.

What we can see here is not debate or dialogue but what Al Gore entitled The Assault on Reason. Focusing on the American political system, Gore writes that our American system of democracy is broken and we must fix it. In a telling passage, he writes: “When fear crowds out reason, many people feel a greater need for the comforting certainty of absolute faith. And they become more vulnerable to the appeals of… leaders who profess absolute certainty in simplistic explanations portraying all problems as manifestations of the struggle between good and evil.” In the above Glenn Beck broadcast, we can see that Beck draws the lines between good and evil, between us and them, very overtly.

In the broadcast, Beck begins with a mockery of NPR, of its perceived elite values, its perceived small audience. At first glance, these attacks seem rather inapropos to his discussion; however, his argument seems to be predicated only on these values-based attacks. The joke is that Olbermann speaks to a small, elite audience about silly, elite things, whereas Beck and his minions are the voices of the people. Fod God’s sake, Beck’s show has over 10 million listeners! Even more interestingly, his only attack on K.O. is over his track record on defending Christianity, which hardly needs defending. Note that this is a different discussion entirely, one that deals with the role the majority faith should play in a plural society. The topic at hand is about protecting minorities from religious bigotry, about Islamophobia. Glenn is disengaging the issue.

And so it has been throughout the entire debate: one without compassionate middle ground.

One side frames Park51 as an Islamic community center in lower Manhattan, the other a “Ground Zero Mosque.” One sees Cordoba as a symbol of interfaith cooperation, the other as a symbol of Muslim domination in the West.

I know exactly where I stand on this issue: I support Park51 and the right of peaceful Muslims to build whatever they like wherever they please. I believe in an America that works towards a building a tolerant society where my Muslim friends and neighbors don’t have to hear about their co-religionists getting stabbed in the street. But to leave the response at “I support _______ because _______” obscures too many of the underlying themes of the discussion.

In analyzing those themes, we take away from the Park51 debate the same thing we take away from Everybody Draw Muhammad Day. That words matter, what we define things as and how we talk about things matters. In a recent Salon piece, bluntly titled “The Media Duped Us,” Sept. 11 widow Alissa Torres details the way Park51 media coverage specifically intended to make victims of the tragedy experts on the debate. Torres recounts an e-mail she got from a New York reporter who was “trying to look for family members who think building a mosque at the site is a bad idea.” Clearly, the unnamed journalist was not looking for just any opinion; he wanted his lead to bleed America. Even the questionnaire Torres receives from CNN asks how she felt about the proposed site being “this close to Ground Zero?”

What is interesting here is that both outlets were looking for a certain type of expert, a pre-packaged opinion to appeal to a certain component of the discussion, mostly likely defined by their ideological target audience. Although we used to define this kind of niche creation as the “Daily Me,” the post-modern implications have become far more widespread. Our media, how we follow it and what media framings we privilege create the “Daily Us.” In internalizing our current events this way, we only educate ourselves to comprehend part of the debate. In discussing the value of dialogue in society, Al Gore states that “the superiority [of democracy] lies in the open flow of communication,” but what we are witnessing are media-created and self-enforced rhetorical divisions. The language we use to define our world matters, for our words define our thinking and our action.

As an intern for Interfaith Youth Core, I’ve been tracking the progress of the Park51 debate for some time, and although the issue has died down as the media moves onto new headlines, the tone has not changed much. We may not quite live in two Americas, but we Americans are ideologically divided. And if my work around religious dialogue has taught me anything, communicating and being heard these days is hard.

In the Age of the Internet, we are bombarded with more media stimuli than we can process. We are lost, separated by a media culture that profits off of those divisions, making us all into tiny niche markets. But if we are to come to some resolution on this issue and foster the change we say we want, we need to at least come to the table democratically, as equals, and engage.

Nicholas Lang is the Communications Intern for Interfaith Youth Core and a Senior in International Studies at DePaul University. Nick just started up DePaul’s first film club, the DePaul A.V. Club, and represents the lone agnostic among 2010-2011′s Vincent and Louise House residents, who represent DePaul’s Catholic intentional living and social justice community. He is also the co-founder of the Queer Intercollegiate Alliance, an initiative between Chicago’s LGBT campus groups; a writer for the DePaulia newspaper; and head of Campus Outreach for the Secular Humanist Alliance of Chicago. Occassionally, Nick sleeps.

Nicholas Lang is the Communications Intern for Interfaith Youth Core and a Senior in International Studies at DePaul University. Nick just started up DePaul’s first film club, the DePaul A.V. Club, and represents the lone agnostic among 2010-2011′s Vincent and Louise House residents, who represent DePaul’s Catholic intentional living and social justice community. He is also the co-founder of the Queer Intercollegiate Alliance, an initiative between Chicago’s LGBT campus groups; a writer for the DePaulia newspaper; and head of Campus Outreach for the Secular Humanist Alliance of Chicago. Occassionally, Nick sleeps.

A Call to Love With Our Feet

September 13, 2010

September 11th is a difficult anniversary. “Love” is perhaps the last word we might associate with that day.

September 11th is a difficult anniversary. “Love” is perhaps the last word we might associate with that day.

On September 11th, 2001, I was fourteen-years-old and ignorant to a lot of what was happening in the world outside of my home of Minnesota. That day was a wake-up call to me, to be more aware of what was happening outside of my own context. To listen more and to learn more. But love was far from my heart.

Nine years later, we are experiencing another wake-up call. The call is the same: we must listen more and learn more. And, with a surge in anti-Muslim sentiment and hate crimes enveloping our nation, love again seems far from our collective hearts.

On Saturday, September 11th, 2010, I participated in a day of prayer and reflection. Granted, I did not pray, but I was glad to be there among those who do. On such a day, little else seems more appropriate than prayer or reflection.

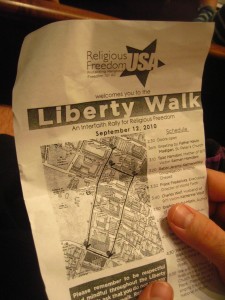

On the ninth anniversary of 9/11, at that day of prayer and reflection, I listened to a woman who was in Lower Manhattan on the day of the attacks reflect on her experience. Through tears, she recounted the horror and fear she experienced that day. But she added that 9/11 was a wake-up call to her: it was a call to love more, not less. She spoke of her God’s vision of inclusion and integration for all people; it was a message I carried with me when I hit the road for New York City just an hour later to attend Religious Freedom USA‘s Liberty Walk: An Interfaith Rally for Religious Freedom.

Yesterday, September 12, 2010, was a rainy day. In spite of the rain, at least 1,000 people came out to march for religious freedom in support of the Cordoba Initiative‘s Park51. We gathered at St. Peter’s, the oldest Catholic church in NYC, to listen to speakers including the Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Father Kevin Madigan, Religious Freedom USA founders Joshua Stanton and Frank Fredericks, author and environmentalist Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, Auburn Theological Seminary President Rev. Katharine Henderson, and Charles Wolf, who was the husband of a 9/11 victim. After being inspired by their calls for inclusion and interfaith cooperation, we took to the streets.

It was a cold and rainy day, but as a diverse group of people of all faiths and none at all walked the streets of NYC arm in arm with flags in hand, it felt like a moment of transformation. It was not “us” supporting “them” — it was all of us, together, walking in hope and mutual loyalty. We were listening. We were learning. We were loving one another.

One man stopped us and asked what we were marching for. When we explained that we were walking for religious freedom, particularly in support of the Cordoba Initiative’s Park51, he scoffed and said, “The whole country’s against you!”

In one sense, he’s right: the road to religious freedom in America has been long and it will continue to be. But he also couldn’t be more wrong: pluralism will prevail. Those of us who walked the NYC streets that day proved it.

Our nation will heal from the wounds we sustained on September 11th, 2001, but we must do so together. Let us extend the call to be more than it is. It is not enough to listen more and learn more – we must, as both a survivor of 9/11 and a crowd of people walking in interfaith solidarity taught me, love more.

Our nation will heal from the wounds we sustained on September 11th, 2001, but we must do so together. Let us extend the call to be more than it is. It is not enough to listen more and learn more – we must, as both a survivor of 9/11 and a crowd of people walking in interfaith solidarity taught me, love more.

The Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once said of his interfaith efforts for the Civil Rights movement: “When I march in Selma, my feet are praying.” At the Liberty Walk, a group of people marched for religious freedom. And though I am a Secular Humanist who does not pray, truly it felt like all of our feet joined together in a common call: to listen more, learn more and, above all, to love more.